By Patricia Voelker

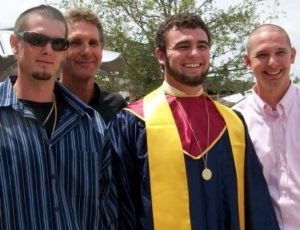

They smile with the sun in their faces in that final group photograph.

My grandson, Kelly McConnell, is at the center, bearded and broad-shouldered and handsome in his high school graduation gown. He stands between his stepbrothers, Nathan and Roy III, while their dad, Roy Jr., hovers just behind them.

Fourteen months later, they would be dead. All of them. They were vacationing near St. Petersburg, Florida, when a drunk and drugged driver ran a red light, smashing into their car at 84 mph and instantly killing my daughter’s family: 51-year-old Roy Jr.; 27-year-old Roy III; 24-year-old Nathan; and Kelly, my only grandchild, who one day earlier had celebrated his 19th birthday.

That’s how quickly it happened. That’s how quickly my daughter, Amy, lost her son and her husband and two stepsons she’d co-parented since they were boys.

Grief is different for everyone. Everyone’s loss is unique. For me, a grandmother who lost her only grandchild, it was as if the future ceased to exist: Who Kelly would marry. What he would become. All the things I thought he would see that I would never see because he was supposed to outlive me. The newsy, upbeat family letters my daughter, Amy, had always sent stopped because there was no longer a family to write about. Our conversations became stilted for several years. I didn’t want to say the wrong thing. So I never talked about anything that she didn’t talk about first. When, three years after the crash, Amy and I were both diagnosed with breast cancer, we faced it without the support of family who otherwise would have been there.

These are the things a 20-year-old took when he made the choice to drive drunk and high on the night of July 31, 2010. He ended four lives, left three women widowed and two children fatherless. He destroyed families, changed relationships and altered futures – including his own. Today, he is serving a 44-year prison sentence.

Time and trauma erase certain memories. Like the details of the call from Amy on an early Sunday morning delivering the worst news I would ever get. Other memories, though, shine all the brighter. Like my last day with Kelly.

He had recently finished his first year at the University of Miami and was turning 19. Roy III and his wife had just had their first child, a boy named Roy IV. They had so many reasons to celebrate as they gathered for a long weekend in a rental house in Redington Beach. I drove down from South Carolina to join them on Wednesday, July 28, and the next day, I took Kelly shopping for his birthday present. We found a cookie cake on sale – he loved cookie cakes – so I bought it for him. Then we went to Kohl’s, where he chose several T-shirts and shorts to try on while I waited outside the dressing room.

I can still see him stepping out to show me how the clothes fit, how trim and handsome he looked. No “Freshman 15” for him, I thought. I sang “Happy Birthday” to him as we checked out, and he wasn’t even embarrassed.

It would be years before I could walk into a Kohl’s men’s department again without feeling sad.

The next morning, the guys and their wives, as well as Kelly’s girlfriend, headed to the rental house with a view of the Gulf of Mexico. Just before they left, I stopped Kelly and made him stand still while I took his birthday picture. I had no way of knowing it would be the last photo I ever took of my grandson. The last time I would tell him I loved him. The last hug I would ever get from him.

As I drove back to South Carolina, I thought about how proud I was of the whole family. How good the McConnell guys were, how I would have enjoyed being with them at the beach.

Amy would piece in the details of what came next. That final day. They relaxed, played games, grilled out. Later that night, the guys headed to see a late movie. The women went to bed. Sometime in the middle of the night, Nathan’s wife woke up and realized he wasn’t home. She roused the other women, and they started calling the guys, but no one answered. At some point, they turned on the TV and saw a picture of a crash scene and a car wrecked beyond recognition.

They called hospitals. They phoned the police, who were already anticipating a call about a missing family. They knew that somewhere, someone was waiting on them.

The woman who answered the 911 call told Amy she’d send someone over to the house to get their information. Instead, an officer and victim’s advocate came to make the death notification.

My phone rang at 7:25 a.m. My daughter’s voice was thick. I knew she’d been crying.

“What’s wrong?” I asked her.

“It’s bad. Really bad,” she said. “The guys went to a late movie and on the way home they were hit by a drunk driver.”

Not yet understanding, I asked how they were.

“Oh, mom,” Amy sobbed, “they’re all dead.”

For the longest time, it felt like it didn’t really happen. That it was just a nightmare and we would all wake up. But it did happen. We had no choice but to face our new reality.

In Florida, my daughter had a built-in support system of family and friends who had known the guys and grieved for them alongside her. In some ways, I envied Amy for that. I lived in South Carolina, where most of my friends hadn’t met Roy or Kelly’s stepbrothers, or they remembered Kelly as a child and not the young man he’d become.

That’s how I ended up joining Mothers Against Drunk Driving. In early 2012, I became involved in a group called Families of Highway Fatalities, which introduced me to MADD. They became my support system. That December, I shared my story during a MADD candlelight vigil, vowing that South Carolina, which has among the most DUI fatalities in the nation, would have its first-ever Walk Like MADD in the coming year. MADD’s signature fundraising event provides a place for survivors, victims and supporters to remember lost loved ones, inspire change and commit to a nation of No More Victims.

It took a little longer than that to put our Walk together, and we didn’t have a clue what we were doing. But in the fall of 2014, we pulled it off in Charleston with the help of incredibly dedicated volunteers, surpassing our participation and fundraising goals. The next year, we held a walk in Columbia, and in 2017, we added a Greenville, SC, Walk Like MADD.

Last year in Columbia, we held our fundraising event at the South Carolina Criminal Justice Academy. Our dedicated law enforcement officers lined up their vehicles out front, and when the Walk ended, they turned on their lights and left to set up DUI checkpoints.

I tell everybody that the people at MADD know what you’re talking about. They didn’t have the same experience or the same loss. But they know what you’re talking about. They understand you’re grieving. Those who haven’t experienced it are there because they understand it could happen to them.

During one of those early Walks, Amy and I passed an area with a cut off. We heard someone crying. I decided to check on them. It was a man and his wife who’d lost their daughter. I must have been there a long time because Amy came up to check on us. The next thing I knew, those two grieving moms had bonded. They still exchange emails.

That’s one of the reasons I walk. Sometimes, you’re really feeling awful but someone else is there to say, “I get it. I get it. What can we do to make you feel better?”

At last year’s Walk, I started out the door when I saw a woman crying. I asked her name. Who she was mourning. She told me it was her son. I grabbed her and hugged her and just let her cry and talk. That’s what she needed. MADD gave us that safe space.